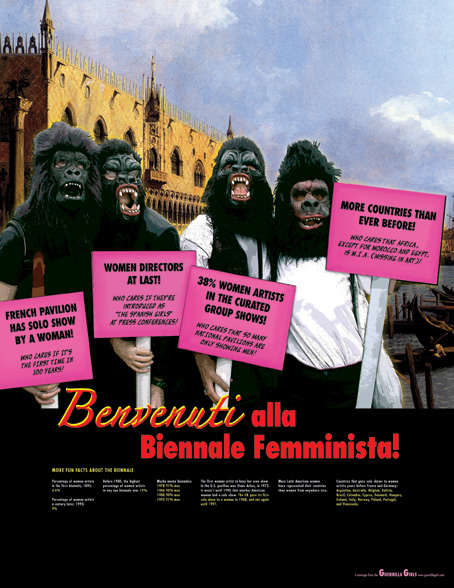

The Guerrilla Girls are completely and totally intertwined with Feminist Methodology. They project that they are women artists, and it is completely a part of their identity. Although they are masked, being a woman is an extremely relevant part of their work. Their gender has completely to do with the prints that they make, and their gender is extremely relevant to their message. In this piece, they are praising the Biennala for doing something right. There is finally diversity, and a lot of female representation, opening the door for female directors, which is something that was a problem before. They show themselves, wearing masks, and holding prints, which would have displayed statistics about the event, and congratulating the Biennala for opening its doors to woman directors. To examine this piece requires great amounts of feminist methodology. For example, this piece would not work if it were made by any other gender. The necessary of the woman artist, working for other woman artists, is important in their narrative. They call on their strengths of the other women, and they band together in an attempt to create change. What is interesting about the Guerrilla Girls is that they usually are calling people out. They go place to place, and try to ignite change for the benefit of woman artists. This creates a community, and a resource for women who had attempted to break into the art world. The fact that they released a poster in a positive light for a place that has done something right is a step in the right direction. The woman are working for other woman, it is important to know and analyze how gender plays a role in interpreting their prints, because not only does it play a role but it is perhaps the most important aspect of the piece.